27 February 2023

Fractal secrets shared in front of the hearth

18 February 2023

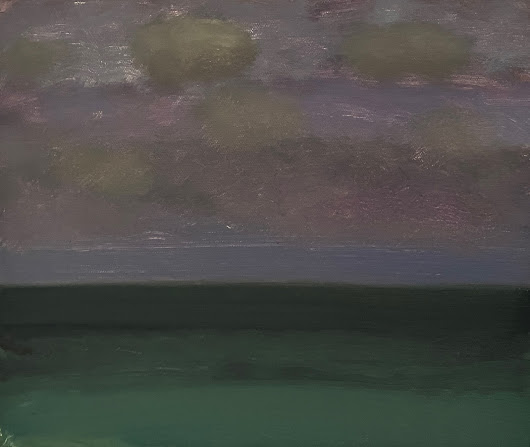

Five paintings, the air but not the wind

So on this evening which was showing great promise, I set up and began to patiently await signs of life in the sky, wondering just what it would dictate for me.

14 February 2023

punished and sent to bed without dinner!

Three dark pictures, taciturn, like naughty children who were punished and sent off to their rooms for misbehaving. They are not happy about it! In fact, they remind me of ME, when I was punished and sent to my room without dinner. Whether we like it or not, it appears that our past will always keep sending us postcards from places long ago that we would rather forget.

But these three were done on a rough and stormy-looking night. In the late afternoon I had driven out to the beach because the sky had looked decent from the house, but darn it, Mother Nature fooled me as it often does because it was overcast. I had had misgivings already when I hit the road and saw the dark sky but, "what the hell", I thought, I had been home all day and wanted to get out. After a ten minute drive I arrived and parked carrying my painting gear up the sweet little path about 60 meters further on to the small dune where I normally paint. The beach was windy and desolate but I set up anyway. My outings there had been sporadic all summer long due to the weather and I really missed these afternoon sessions.

Though a bit confused by the form of so many clouds all jumbled together into a flat pile, I nonetheless jumped into the first painting above without too much thought and I quickly lost my way,. .. Ha Ha,... and so much for rigorous restraint. Remarkably though, I was able to 'bring it back' and save it by turning it into something I had not at all anticipated. It's now not at all unpleasant but just something very different than what I had had in mind.

In fact, though surprised, I was reasonably happy with it, but the weather discouraged me from beginning another one from this dark and difficult sky. So I brought out two older studies which I had brought to see if I could also 'bring those back from the dead' and perhaps put them into an acceptable state.

But there is something about these two older paintings (below) that make them somewhat unusual. When they were done (years earlier) they were not quite right, either just plain boring or perhaps just 'unfinished' or 'unrealised', which was what I actually felt about them. But anyway, they were unacceptable and worthless to me in their present state. No drama, this happens all the time to paintings. Often, paintings will either get better with time or worse. Unlucky paintings might appear great when just finished but over time they quietly fall off the podium and end up in the leprosy ward. Still others might look awful when just painted but improve with age like a bottle of whiskey. It's really out of our earthly hands, and as any artist knows, the Gods regulate all this stuff in the end.

But these two were rather mediocre, somewhat lifeless from the get-go and whether as Dr Frankenstein or Doctor Good, my desire was always to give them a life of their own.

So over the past few weeks I have begun pulling these poor things off the shelf a few at a time and putting them into the boot of the car with the rest of my painting gear. When I have finished a session and my palette is drenched in colour, and importantly, if the skies seem to vaguely line up with an idea, I will put them on the easel, look at the motif, and throw colour at them to see what comes of it. What is that expression for politician's behaviour so prevalent on CNN roundtables these days?

"Throwing spaghetti on the wall to see what sticks?"

After all, I have nothing to lose. Sometimes I pull it off while at others it's a lesson in exasperation.

But Painting is not a zero-sum game as many seem to understand the rest of life to be, (mostly financiers to be honest). Still, the native American Indians (who are still a wise bunch) often quip:

"Sometimes you eat the bear, and sometimes the bear eats you". It has nothing to do with a zero-sum game at all, its simply bad luck.

In any event I am reasonably happy with the first painting below, though there is that bit of scruffy-looking light on the righthand side that I might still tone down ever so gently if I get to it.

But I am really happy with the one below it, for it came out just right, to my complete surprise. And it was ALL just good fortune, really good luck, because this time around, the E.R. doctor inside me managed to revive this cadaver. But I have no idea how I did it. It happened so quickly, perhaps within ten minutes. It was done like in a dream that one quickly forgets upon awakening. It comes at the surprise end of a long trek home.

There is much to say about all this but it will have to wait for the next time to go further into this subject of what constitutes the idea of 'Finish' when considering a painting.

Anyway, I always learn so much by going deeper and deeper into a picture, almost against my own instinct, like a cave inside myself, deeper and darker, until I feel as if I am back in my childhood bedroom again and still being punished without dinner.

07 February 2023

Dreams and reality On Chesil Beach

But how one awakens to the great Reality of what we call Life is also quite varied, and it's also kind of mysterious, especially as one ages, but then many of us for some reason, never awaken to reality at all, regardless of our age. To me Life is a great parade, marching in it, or watching it, oftentimes between the two.

But, anyway,,, I love really good authors, not the cheap-reads but the ones who take us to a space where we can be confronted with Reality, the ones who show us where they fell and how got up again.

And this is equally true of the Arts in general, but I'm mostly thinking of how really good painters can also move us into this space of a wide reality through their own failures and successes.

From the very first page of this wonderful and intimate book I was transfixed and transported back in time, to a Britain I had never even known. McEwan has the power of narrative and not unlike a great painter, he has a love for detail and mood. I highly recommend it for anyone, who like me, hasn't yet discovered this side of postwar Britain.

Ian McEwan paints a picture of a complicated and unified order that is just on the verge of a social earthquake. I had seen lots of great British films, the edgier ones from the 40's and 50's that foretold the social unrest of the 60's to come but I had not read too many books about it. The 60's in every way, was a collision of several great forces that changed the landscape.

Painting of course, changed dramatically like everything else as it went POP! But this movement seemed like a shallow display of ostrich plumage though I know many would strongly disagree. And hey! Who cares in the end? With perhaps the exception of Bacon and Freud, most visual artists went for the flashy gag which they managed to sell!! Silly money that made a few savvy investors wealthy.

But getting back to the world Painting, I ask always, how does a painter render a narrative, a voice, or a mood for instance? Is there a technique, or does it lie-in-wait, deeply inside a painter's soul for the right pictorial idea to surface at some point in his life?

What I often think about in Painting is the specificity of detail that never bogs us down with tedium but lives in a generously grand operatic space. Ian McEwan paints this British social landscape with an eye like Chardin, but better yet, maybe Pietro Longhi with a twist of Goya thrown in.

Like a great writer, a great painter depicts the world at large by pulling it apart then only to piece it back together again whole and fresh as if by magic. The result is not a copy but an entirely new and believable world for the rest of us to experience. And with the subtlest of skill, his character development in On Chisel Beach pulls us into his drama within barely a few sentences.

This reminds me of why we love Vincent Van Gogh's paintings so much. In front of his work we surrender ourselves obediently and give him the power to yank us into his feelings without a hint of defiance. He was that kind of painter, absolutely unique, he was a bonfire of feeling. Sometimes when I hear old scratchy recordings of Blues singers I feel heat from the same bonfire.

Don't we succumb to this because we have been seduced by his empathetic persuasion towards his characters like we do for an author? Both the artist and author seem to cast a spell over us, the really good ones are witch doctors while the bad ones are priests.

Lastly, and speaking for myself; why am I so much more moved by Truffaut's The 400 Blows than I am about my own childhood experiences of family life and boarding school? Is it not that Art pierces both dreams and reality by recreating the concrete out of our own abstract memories?

And what is it about truth and fiction in this space of memory in which we all live together, but separately? And how does a work of Art, a book or painting in these cases I have cited, possess the power to transport us to a particular place in ourselves that we recognise even if we have not yet been there? So many questions....